In place of a Foreword, or an imaginary interview with the curator

József Szurcsik

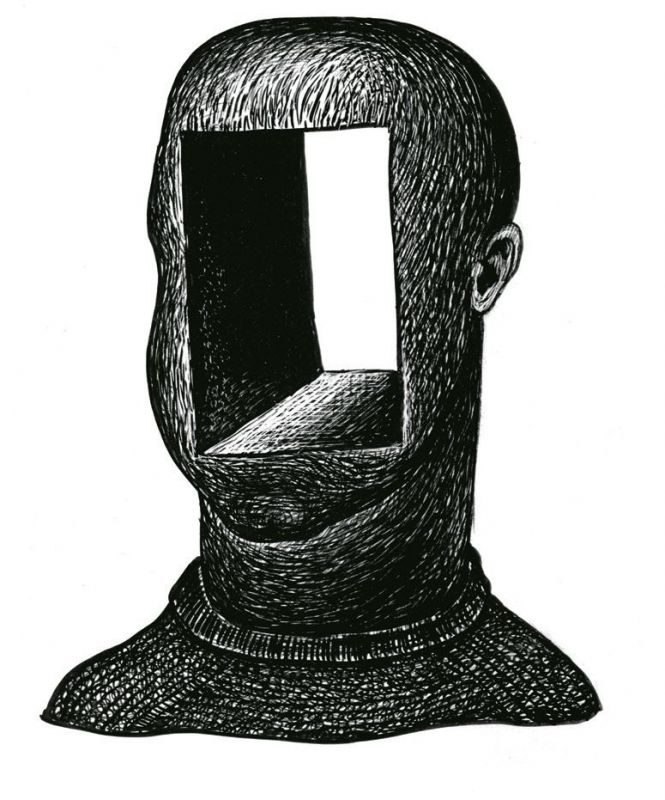

Szurcsik József: Bestiarium humanum sorozat

2017-2018, tollrajz

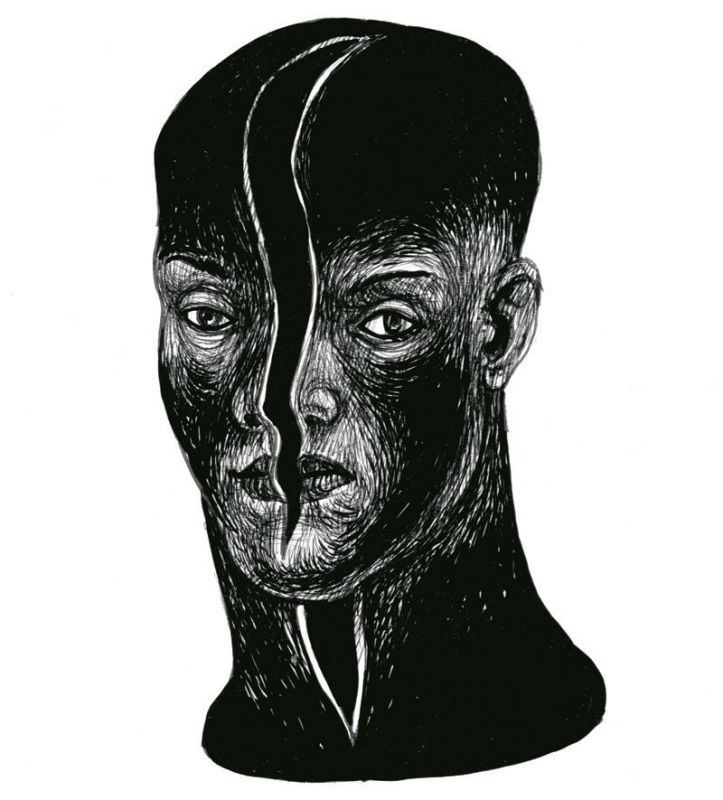

Szurcsik József: Bestiarium humanum sorozat

2017-2018, tollrajz

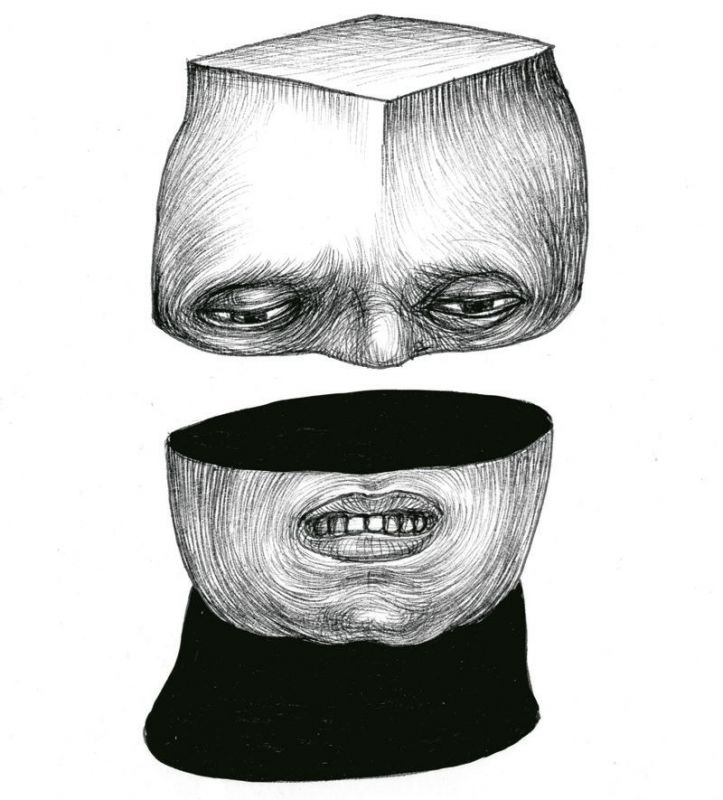

Szurcsik József: Bestiarium humanum sorozat

2017-2018, tollrajz

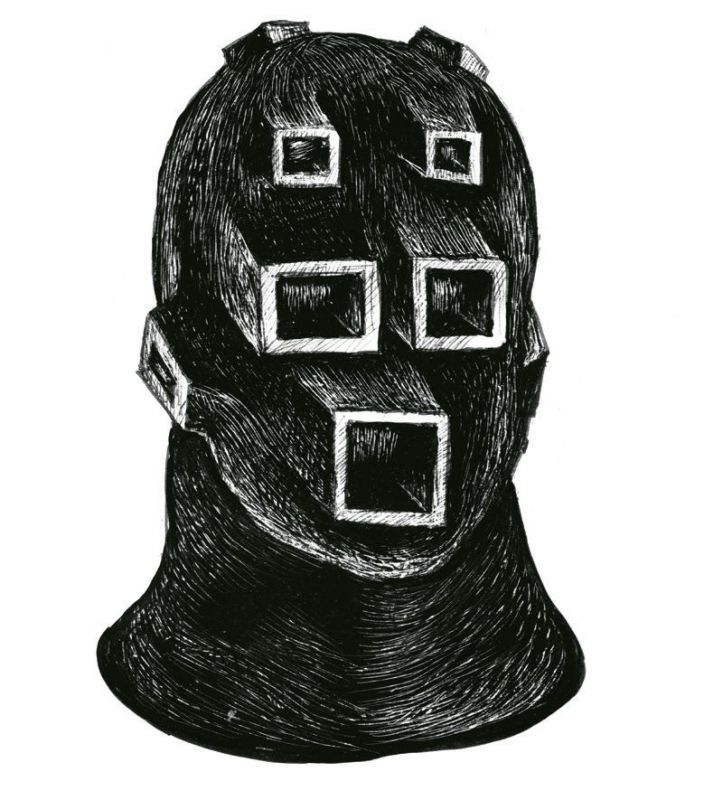

Szurcsik József: Bestiarium humanum sorozat

2017-2018, tollrajz

Szurcsik József: Bestiarium humanum sorozat

2017-2018, tollrajz

Szurcsik József: Bestiarium humanum sorozat

2017-2018, tollrajz

ARTONOMY – SECOND NATIONAL SALON OF FINE ARTS, 2020

In the early days of January, on an anxiety-prone and fog-smelling weekday, I headed for the Műcsarnok. I’m wearing the obligatory items: scarf, hat, gloves. I was approaching my destination with rushed but resolute steps; if anyone who knows me saw me like that, with my body leaning forward and defiantly pressing ahead, they probably thought, certainly, this guy is definitely going somewhere.

They were right.

When I arrived near the imposing building of the Műcsarnok, I looked up to see if there was some hopeful light filtering through the gloomy clouds and the glaze of urban fog, but there was none. I did see, however, the emblematic inscription finely carved in a Romanesque font under the tympanum:

“TO HUNGARIAN FINE ARTS MDCCCXCVI”

Hmm, I thought to myself.

I shuffled up the steps and entered the building. This time I tried to look at the well-known exhibition spaces as a curator, to see and feel the venue of the exhibition-to-be. I paced up and down the halls, visions battling in me with emotions, numbers with numbers, metres with metres, personal and impersonal variables viewed from this and that angle, even the possible and the impossible were battling in me, but in the end they all reconciled in an amicable handshake somehow, I don’t even understand how.

In one of the halls, where the works of the exhibition running at the time were lined up on the vast white walls, a visitor, a well-dressed elderly lady, slowly and thoughtfully took one step, then another, stopping in front of the pictures, and as I got closer to her, she turned to me and with a glowing face and elated rhythm sprang the following question on me:

“Isn’t it wonderful?”

I must have made a surprised face, so she went on, as if explaining her previous question, intended to be rhetorical: “These works are simply fantastic, don’t you think? Incredibly high quality, brilliant works able to capture miracles even… This is the kind of art young people should be shown as an example, they are worth learning from, works like this should be shown and discussed on television, not all that nonsense that muddles up people’s thinking! But this! This is simply wonderful, am I right, young man?”

Having said that, she turned her gaze towards the pictures, continued collecting the visual experiences, happily filling herself with the impression created by the artworks.

I went on too, planning, scribbling, examining the space, virtually darting back and forth between the rooms. Half an hour must have passed before I went back to the previous hall. This time a middle-aged couple were standing before the pictures, at the exact same place as the elderly lady previously had been. I thought I would quietly pass behind them, lest I disturb their ecstasy. And then I overheard a powerful fragment of their agitated conversation:

“This is just incredible! Isn’t it? How can anyone come out with something like this? Is this art? Does anyone call this art? And should something this tasteless be exhibited at all, put on public display? How horrible!

It’s giving me the shivers.”

Complaining and outraged, outdoing each other in their moaning, they walked off.

I stayed there and took a step back to have a good look at what had caused a catharsis in one person and the heebie-jeebies in two others. I couldn’t find the solution, except for one thing: the defining presence of the difference in tastes. Visual stimuli trigger emotive responses in people and this little story provides a subtle picture of the differences between decoding visual messages. It is differences between tastes that underpin the peculiar patterns of acceptance of difference, among other things, and it is based on this that things get resolved or escalate in various micro-environments and at the level of society too. Of course, all of this is not the work of the devil but completely natural.

What I learnt this morning was that no matter what exhibition installation we choose and how successful it will be, no matter what great works we’ll exhibit and fine-tune with one another, it won’t be liked by everyone.

Following from its nature, a salon exhibition does not stand a chance of being assessed objectively; there won’t be peace because it’s impossible to satisfy everybody’s preferences at the same time. If anything is impossible, this definitely is.

The National Salon exhibitions in the Műcsarnok are important events in the Hungarian fine art scene. How would you describe this milieu?

In the past, salon exhibitions were prominent events in the lives of artists. No wonder, since they rarely had the opportunity to exhibit and there simply weren’t any exhibition venues providing the right conditions apart from central venues like the Műcsarnok, which was never available for all the artists who wanted to show their works to the public. I’m talking about those days when there were no longer and not yet any private galleries. So the opportunity for group exhibitions at venues like this, in exhibition halls like this, was crucially important because there was practically no chance for artists to have solo shows. Obviously, this is how the Salon gained importance for a great many artists: thanks to the display of a rather large body of material by the individual artists, individual achievements could be seen here, displayed next to each other, in a collective environment. Their graphic sheets and paintings made it to the public displayed on the walls of the Műcsarnok, and sculptures were happily posing in the spacious halls.

Salon-type exhibitions, however, were never complete, despite their spaciousness. For this reason or that, some artists or communities were always ’left out’. Nevertheless, being the curator of this exhibition, my objective is to present to the public a material that is as extensive as possible within the available space, and draw attention to similarities and differences, creating a balance in difference.

There were always opposing views and trends but nowadays the division in the fine art scene has become especially stark. It happens that some artists with a non-conventional, innovative approach, most of them young, turn against the middle-aged and old artists, who they often see as conservative and outdated, viewing them as ’ancient fossils’. Other conflicts, to just name a few, include that between figurative and non-figurative, objective or conceptual artists, but even between self-reflexive, individual artists and those who are committed to social issues having embarked on a social mission, between successful and less successful artists, between those who earn a lot – how mundane – and brilliant artists who are financially worse off, and between the variations of all these factors. I left the attitude of artists to the incumbent powers last: some are neutral, some are in opposition, and some are more or less sympathetic, even privileged and promoted; and there are those that the system idolises as an embodiment of its ideology.

In this Salon, I wanted to highlight cooperation rather than division, to emphasise the indestructible, mighty fortress character of fine arts.

Is it worth organising a salon exhibition these days, and what lies behind the debate on the need for salon exhibitions?

I don’t know.

What different people think is strongly influenced by the patterns they live by, and these partly depend on their social backgrounds and their prevailing tastes as well as the influences of their micro-environments.

There are those who were raised with traditional middle-class homes with classical furniture, paintings and sculptures; that was a given for them, they grew accustomed to or chose such an environment and like it, perhaps they can only feel comfortable in such environments. My home is my castle, goes the saying, but it might be the opposite: anywhere else but home. A lot depends on individual dispositions and experiences. Some people would get the heebie-jeebies in a classical environment and would, let’s say, only feel a Bauhaus type interior, furnishings, forms design and fine arts ’appropriate’ to their own home. And there are those who see this as empty rationalism, self-seeking, rigid and regulated and, rejecting it, they only feel at home when they are surrounded by, let’s say, furniture made of upcycled pallets. What lies behind the problem and the continued debate is that starkly opposed opinions are imbued with the differences in taste, emotions and even worldviews, and they clash on these and not clearly professional grounds, in which case the opinions and arguments of the ’other parties’ are mutually heard.

By the way, taste.

What we see as good or bad, beautiful or ugly, is a matter of perspective.

During a process of evaluation, the final position of a given subject is either determined in the best-case scenario by taste, and in the worst-case scenario by jealousy.

Being curious about differences, accepting them, recognising them, respecting them, and the opposite – not accepting, not understanding, rejecting, feeling antipathy and even hatred towards them – all spring from the above; everything hinges on emotions, individual preferences and social background.

In several respects, the debate on the salon exhibitions is a debate on taste, and in this particular case it has two clear poles. Those opposing the salons say that exhibitions like these are not based on a specific curatorial concept and as such are unable to provide a harmonised picture based on correlations; there is no curatorial selection without a curatorial concept, and only an indiscriminate list, a festival-like presentation – often lacking taste – can be realised. In this take, individual achievements are bound to be seen as fluctuating and heterogeneous in terms of artistic quality; works are virtually heaped together without context or played off against one another.

Artists who are in favour of the salon exhibitions think that one of their strengths is their heterogeneity and the fact that they look back on a period of time in the past, which in this case is five years. In their view, the present is brought into focus through earlier works of Hungarian fine art, i.e. individual achievements, which is important because it helps us form a realistic picture about artistic qualities, trends and individual paths, thus contributing to providing a snapshot of the present, while outlining the period and its developments, which, in the end, can be defining for the future, when we look back to this period in a few years’ or a decade’s time.

So, should there be a salon or not?

Let’s take a look at what would happen if the “no salon” won in the “salon or no salon” debate.

In that case we would have cancelled this year’s salon and deprived a large part of the artist community of an important opportunity. As a result, they would be justified in demanding to hear a reason for the lost opportunity to show their work to the public and saying that nothing ever works normally in this country.

So is it better for artists not to have a salon exhibition?

We must admit that in the current geopolitical situation it is far easier to stop something than to replace it with something new.

If the salon debate were won by the “yes to the salon” side, it wouldn’t appease everybody either.

The salon-supporters often ask: Is there any other solution that would give the public the chance to see such a broad and realistic overview of the contemporary fine art scene?

This year’s salon exhibition has been built but the organisation was done at a very tight pace. Why?

There were impossibly short deadlines imposed on the organisation of this year’s exhibition. Of course this deservedly aroused dislike in our colleagues, we got harsh and less harsh criticism. One of the reasons behind the rushed work was the coming renovation of the Műcsarnok, which cannot be put off any more and is due in the second half of this year. As far as I know, it was on the cards before Christmas last year that the building would be closed because of its poor technical condition. No one knew what would happen and the planning and organisational work could not begin without the project being given the green light. This is why we had to start work under such tight deadlines.

What’s your take on people who didn’t want to take part in this year’s Artonomy exhibition because of ideological reasons?

The guiding principle of this year’s salon is “exhibiting side by side” and it propagates solidarity between artists instead of discord, while more than anything it focuses on artistic quality. One either stands by somebody or something, by our common goals, for the transparency of the artistic public life and for the prestige of art or they can leave the team and leave the game, etcetera.

This is why I find it important that, despite all the difficulties, having recognised the real meaning of our genuine intention, the invited artists have the chance to contribute to the realisation of the exhibition with their works in order to promote the autonomy of art.

Those who oppose the salon exhibitions decided to stay away for various reasons. One of the main ones has its roots in principles and/or worldviews and political convictions and is linked to the fact that the Műcsarnok is owned by the Hungarian Academy of Arts.

The other reason is also ideological in nature but is only critical of the name of the exhibition, i.e. the words ‘national’ and ‘salon’, taken separately or together.

The third reason is that ours is a group exhibition, where – according to the opposers – a medley of works is displayed, lacking uniformity in regard to the character and quality of the pieces.

The fourth reason concerns the actual fellow exhibiting artists or an antipathy for and lack of acceptance of their art.

The fifth reason is that some artists don’t have artworks ready or available for exhibition, e.g. they are displayed somewhere else.

The sixth reason is permanent residence abroad or illness.

A loyalty to principles was clearly, emphatically and rather consistently expressed by the opposers of Artonomy, which is of course to be respected. However, I have regrettably no positive experiences neither in regard to openness, nor to efforts made by these artists to change the current situation, nor their willingness to cooperate. This is a very big problem. I’m sad to see how things are.

What could be at the heart of the problem?

There’s no doubt that exclusion continues to be decidedly present. In cases when artists turned down our invitation to participate in the Artonomy exhibition, we could ask who excludes who and from what?

Freedom is scarred, in many ways.

Do people see obstacles around them and keep building higher and higher walls around themselves and others? This only leads to growing resentment and more and more fear and anger filling our already aching hearts. Why can't we work together to change this present inertia? Why don't we work together to put this cause back on track?

Why don't we all inspect ourselves and vouch for change, without delay.

Why do some artists ask others if it's alright to exhibit their works in an institution ‘owned’ by the Hungarian Academy of Arts?

Where is the power of free will?

Why does it matter in some people's decision-making “who else exhibits” at a group exhibition?

Does the same scrutiny apply to other prestigious exhibition venues, either in Hungary or abroad, the financial and political background of which are not known but where so many others exhibit their works? Or does this scrutiny only come into focus in certain cases?

When some excellent artists make themselves and their excellent art absent in the Műcsarnok by refusing to participate, they also deprive themselves of the chance to take part in finding a solution and contribute their arguments, and all they prove is that they're unable to work together with those who think - or are believed to think - differently.

Really, what’s the point of this attitude?

Why choose deterioration and demise instead of cure and recovery? Why - and to whom - is it worth pursuing the path of exclusion, mud-slinging and in the end destruction?

Is it no longer possible to build bridges?

The way I see it now, more and more as the days go by, the situation is increasingly reaching the state of being beyond repair.

Society is not only in poor health but the diagnosis is imminent death.

Incurable.

I had an idealistic plan.

I was hoping that it's possible to talk about art, think about art and appreciate the most diverse artworks without dragging party politics and radicalism - in a political sense - into it? I believed that by standing by each other, we can declare: everybody has the right and a place in this country, not only those who believe in “one truth alone”. I was hoping we could change the bad practices of the past and put an end to division with tools of our own, at least in the community of fine artists, and we could show an example and bring hope.

I thought that with all its pain being together here and now would bring together positive energies and that would bridge differences, so, finally, we would not be governed by dissonance and suspicion but these energies would reinforce each other and give art its freedom back.

I trusted that the hate-mongers would have to face an astounding situation and realise that their efforts are in vain and no one supports their scheming.

I was wrong.

Does this year’s selection guarantee a high standard of artistic quality?

Even when the works represent high standards and value, the exhibition will never please everyone, and will not be accepted by everyone. It's simply because any one of the works could be positioned differently in relation to each other, the emphases could always be shifted, and the overall arrangement could be different. It would just be another version, the same works in another context. Would it make the exhibition better? The other version would be accepted or criticised just the same, but by other people. And this could go on and on. One of the key issues in connection with the salon exhibitions is exactly this, since there is no answer and no solution that would be endorsed by everyone.

What does a curator go through when he selects the exhibition material?

I formed the first and most important impression when I saw the reproductions that were submitted. I saw one excellent work after the other and being overwhelmed by it all I tried to build the exhibition in my head. The feeling that this would be a really great exhibition was rising in me and brought a permanent smile to my face. It was pure delight to have to pick out the works from such a rich selection. I was driven by an intense joy and excitement, and this became a dominant experience. I felt that we would be able to build an exhibition that would be perceived by the artists, the visitors and the art profession as clearly laid out, understandable and decidedly up-to-date.

At this point, I’m totally immersed in this project and cannot yet take a step back to see it objectively, but it was a real joy to work with these artists and these artworks. Artonomy will be a lasting memory for me.

And what about emotions? Do they influence decisions?

No matter how you look at it, an exhibition of this scale and dimensions will not please everyone. I would say that some resentment is guaranteed and unavoidable. The artists whose works are exhibited here may feel a certain anxiety if those who decided to stay away think negatively about them and those who were left out might feel envious. Quite a few artists from among those who are staying away from the Műcsarnok and Artonomy because of their principles would have liked to take part but they couldn't lest they bring on the antipathy of their fellow-thinkers for being "disloyal", which I think is a misinterpretation of things, and forced to face consequences. There are some artists who are not afraid of such repercussions, yet they decided not to participate. For professional, personal or ideological reasons, they simply didn't want to have their art 'compared' with that of others in an environment of autonomy and diversity, and they didn't want to see their art displayed alongside that of others.

This is a heavy burden. Everyone has to carry their own cross, and there's no help, there's no way out.

So in this sense, freedom is an absolutely relative term.

Why did you take on the curatorship of the national salon of fine arts?

When György Szegő, the director-general of the Műcsarnok, asked me if I would be the curator for this year’s fine arts salon exhibition, I was dealing with complications after my eye surgery and my condition was fragile. Despite these personal problems, I said yes to him.

I had several reasons. I feel a certain responsibility for what’s happening around us, for or against us, with or without us. I’m thinking that our common affairs in the fine arts could take a turn for the better.

I said yes to curating this exhibition because I take a definite interest in differences and similarities [between artists and artworks], and I think it’s an exciting challenge to bring it to the public through a selection.

I said yes despite the fact that I was well aware I virtually had to do the impossible.

It seemed an impossible undertaking for two reasons.

One of these is the already mentioned tight deadline. The lack of time was a problem because we had to carefully harmonise extremely complex and disparate components, and we tried to realise an exhibition with the participation of an extremely large number of artists.

The job ahead of us looked terrifying, or rather like a premeditated suicide to be carried out with extreme violence.

But I didn’t regret it.

I said yes to being the curator because I believed it was a job intended for me. I came across it, it found me, and I didn’t turn my back on it as I thought I would’ve been a coward if I had done so.

I said yes because if there was no time to develop a well-planned theme to build the project around and ask artists to make new works around, then at least we could ask the invited artists to bring their freely chosen works, which they feel are the most important, and display them at a sincere, open and playful exhibition.

I said yes because I wanted to exhibit the broadest possible spectrum of the output of contemporary fine arts but it was also important that the arrangement of displayed works would not be determined by my personal taste.

Is there a curatorial concept, and if there is, what is its essence?

I already had an idea at the very beginning of this madly rushed planning that I wanted to further develop and present to the professional circles of fine art an embryonic concept I had been thinking about. This was based on the notion of “exhibiting side by side”, and I wanted to apply this specifically to our present age and time.

I wanted to invite artists whose oeuvres would guarantee the realisation of a comprehensive show of contemporary Hungarian fine art, and whose works, exhibited together would bring an authentic and realistic picture of the state of the arts. It was my ambition to include a range of artistic attitudes manifest in the art of the different generations.

Were there any priorities and obligatory expectations expressed by the Hungarian Academy of Arts, the Műcsarnok’s controlling authority?

I didn’t get involved in any obligatory rounds but there weren’t any expectations such as what was appropriate and inappropriate, who I had to invite, who I should “definitely not omit” and who “I wasn’t supposed to or allowed to invite” to exhibit.

Whether you believe it or not, there weren’t any constraints imposed on me.

Of course I invited artists whose artistic qualities are crucial to the Hungarian fine art scene. This circle obviously included artists who had previously stated that they would never step foot in the Műcsarnok. Every invitee had the chance to decide if they wanted to accept or reject my invitation. In the final balance, my ultimate aim was to be able to exhibit high quality works through which I would be able to present to the public as complete a picture as possible about the fine arts and about the times we are living in. Some artists didn’t wish to participate and it was up to them; they sent a message about those who prefer discord to cooperation. Unfortunately, there are a lot of excellent artists among those who weren’t invited. But it’s absolutely impossible to exhibit all the works at one exhibition. This is one of my biggest heartaches.

The other one is that the works of those artists who were invited but turned it down cannot be seen here. At this very moment it cannot be predicted how the overall picture of the exhibition will be affected by the absence of those who demonstratively stayed away. What is certain is that they are sorely missed and they will change this overall picture. Valuable and important works will be displayed but similarly important other works will be left out, so the overall picture will be lacking.

Those who refused to contribute on ideological grounds have deprived themselves of the opportunity to effect change; they must think that change is possible not through the concerted efforts of artists but through the active support of the current political leadership, or rather the removal of the current government, the political authorities and all the affiliated institutions.

Refusing to participate in this exhibition is an act of protest. It is a message addressed to the controlling institution of the Műcsarnok: the Hungarian Academy of Arts, and through that to the government in power. Those who decided not to participate in Artonomy because of the academy’s control are of the view that unless the current establishment leaves, there is no chance to speak of unity, consensus and a united front in Hungary, not even among artists; that is, neither in questions regarding worldviews, nor in professional, artistic matters. In their opinion, it’s not possible to find common ground for different views, nor is it necessary because the time has not yet come for change, because everything in the wide world is governed by interests...

The sad truth is that in the meantime division is ’working excellently’ and continues to grow.

What does the exhibition title mean?

“Artonomy” has different possible interpretations and is a broad enough category to allow all the exhibiting artists to find the right context for their own autonomous expression. I am basically not mainly – or rather not only – interested in works that ‘rhyme with each other’ but those – or also those – that don’t. As I see it, a salon exhibition in 2020 should be seen as an event, a celebration of the fine arts, a demonstration of unity rather than division.

Speaking of celebrations, I would compare the structure of this exhibition to a cake in which the different layers of the profession are nicely and carefully laid over one another. This cake includes the different generations like bits of candied fruit or fine-grain seeds, covered with cream, marzipan and whipped cream. In this way, all the flavours of today’s Hungarian fine art scene are together in one, a whole range of delicacies in one place, a delight to the eye, beautiful, desirable and intriguing.

The technical conditions available to us don’t allow us to present the whole cake at the Artonomy exhibition; there’s simply no extensive enough venue and so only a slice of the cake can be served. We only cut a slice out of the cake but that slice has all the flavours and therefore it will be representative of the whole. This slice will have the same flavour and texture as the rest.

And this brings us to the next overreaching problem.

If too thin a slice is cut form the cake, the gastronomic experience will not be complete because let’s say the nuts, a chocolate chip or raisins will be left out, even though these are part of the whole cake. So it’s guaranteed that there will something missing.

This brings us to the third problem, one to do with taste.

If, for example, someone doesn’t like raisins, their enjoyment will be overshadowed by the fact that this imaginary cake has a lot of raisins in it. Another person might love raisins, so there will be a huge difference in how they experience the cake. I could go on like this, saying that some people love/don’t love or eat/don’t eat marzipan, chocolate, cream or candied fruit, but I won’t.

The point is that whatever I do, this exhibition won’t be good enough, no matter how much I’d love it, it won’t be accepted by everybody, for the simple reason that people have different tastes, to name but one.

How could the reception of the exhibition be made more varied?

It would make sense to organise a pop-up exhibition series at different venues in Budapest. But the exhibited material in the Műcsarnok could even be changed a few times by including new artists, groups and projects. I think that would help.

What was behind the potential success of Artonomy?

I looked at this exhibition as a job to accomplish. I thought it could be nothing else but good because I wanted to show things as they are – the reality created by today’s Hungarian artists through their works – no more, no less, nothing better and nothing worse. As a university teacher, it’s always a great experience to see individual achievements at the annual reporting exhibitions. It’s the same with degree project exhibitions: mind-blowing projects are made and displayed nicely, side by side. There’s never a central theme or concept, only individual achievements and works.

Of course sometimes there are subtle fluctuations and at other times huge differences. Some works are monumental and others more intimate and subdued, but that’s completely natural. Exhibited together, they multiply the experience and provide a basis for examining the period in which they were conceived. Emphatic and resigned works are equally important in outlining the picture of our contemporary world.

Does this year’s salon exhibition represent a particular approach? What inspired its organisation?

My approach was mainly inspired by the group exhibitions and desk critique shows at the university, as well as by large-scale, extensive shows at museums.

My ambition was to present a fair cross-section of the contemporary fine art scene with parallel trends as well as with works of artists with subtly different ways of thinking or attitudes who embarked upon their own paths.

In addition to highlighting the differences, it was important for me to have as comprehensive a list of participants as possible and show their unified support for each other – this is also demonstrated by the “exhibiting side by side” – to enhance the prestige of the fine arts among other things.

There is a minimum common ground, something that all artists agree on, something that will never be a subject of debate between artists: the freedom of artistic expression.

The autonomy of art is a moral law.

The Műcsarnok belongs to us all; in other words, this exhibition venue belongs to all those who exhibit their works in it because the living space of fine art is a suitable and worthy exhibition space.

This sounds like a manifesto.

Exhibiting the works of the invited artists together at this venue is important for several reasons.

Division and boundaries defined by different worldviews have not only made professional cooperation and a ’passage’ from one side to the other difficult but have been standing in the way of joint art projects, i.e. in the way of normal operations.

Artists have lost their faith, which makes them feel dejected and continuously narrows down their freedom, slowly making their lives impossible.

Unfortunately, this is what you can expect in today’s Hungary with its divided society. No wonder the fine art profession’s self-regulating reflexes virtually bring artists to a standstill, when the exact opposite is needed.

It’s not worth using the tactics of retreat as a sign of resistance, going silent or waiting in hiding; on the contrary, artists should pursue their art exploiting it to the maximum. Time is passing and in the final balance what’s important is the artworks they make. There will always be people claiming to be ‘in the know’; they come and go but art remains.

Winds might blow from all directions and there might be storms but I believe that nothing can sweep away genuine, true art.

If we don’t want a schism in the fine arts scene, which would irreversibly lead to the break-up of personal relationships, friendships and for now successful joint projects, and if we don’t want gaps to widen into impassable gulfs, then let’s act together for art and its free flow, and against social division.

I said yes to being this exhibition’s curator because I hope that through my work I can be part of contemporary fine art taking its rightful place, in the spirit of a professional solidarity free from division, preconception and exclusion.

It was my objective to not allow the profession to be pervaded by politics, and have the strength to cleanse the entire fine art scene from the warning signs of it being politicised. This doesn’t mean that artists shouldn’t express their worldviews or political views. On the contrary, no artist should go silent, or hide even in times when the political environment doesn’t reflect their taste and convictions.

That’s how simple it should be.

Can this be the lesson to learn?

Artonomy can teach us many lessons. My own personal experiences are extremely useful. Let’s take the job of a curator. Salon exhibitions traditionally don’t have curators, nor themes, or invited guests, but projects can be submitted by all and a jury selects the works to be exhibited; the exhibition space is covered from the floor to the ceiling and everyone can find the works they prefer, if they are able to look through the myriad of works on display.

The theme of Artonomy clearly defined the curatorial concept and, breaking with previous practice, the show was based on invitation. Let me mention here that the salon exhibition five years ago, titled Here and Now, curated by Júlia N. Mészáros, basically opened the way for a transition from salon type exhibitions to curatorial exhibitions.

Yet, this time we had to deal with a completely new situation; we had to start from scratch but we were able to incorporate the experiences of the salon exhibition five years ago.

I’ve been the curator in many fine art projects so far but I’ve never had to deal with such a large-scale exhibition, mobilising as many artists as this one.

When I sat down to think of a list of potential artists whose works would be exhibited, I didn’t have to think too hard and I put down almost 800 names, artists who all produce important and high quality works. I unfortunately had to streamline this list and adapt it to the venue; it felt as if I had to squeeze eight feet into one shoe and do it immediately. Almost randomly, I had to half the list and then half that again.

This was the most painful part for me in the entire project, and I’m sure I’ll have sleepless nights for a long time to come. I tried everything I could, experimented with as many variations as possible. No matter how I look at it, no matter how positively I want to see it, I must admit that excellent artists have been left out in great numbers.

It’s part of a curator’s job; being a curator means making enemies and friends, people kept telling me.

I had no previous experience of how rational and fair decisions can be made in a project that is so controversial, ridden with so many problems and tensions and arousing such strong emotions as this one. Moreover, I had to make sure that no fundamental values would be damaged, and the final result should be as flawless an exhibition as possible.

Finally, let me talk about something that made a very good impression on me in addition to the excellent artworks and the positive experiences of the exhibition: the welcoming attitude of the Műcsarnok, their openness and faith in me and my ideas, their support rendered as much as the circumstances allowed it, and, most importantly, giving me a free hand. I want to thank György Szegő, the artistic director of the Műcsarnok, and the staff of the museum for trusting that a salon exhibition like this one, perhaps one unusual in its character, can be realised.

Artonomy was an instructive experiment expressing many truths and its final result taking shape – with its virtues and flaws – in the exhibition space from 28 March to 28 June in 2020.

I want to thank the exhibiting artists for loaning their works.

I want to thank Mária Kondor-Szilágyi and Júlia Szerdahelyi for their painstaking, humble and tireless work. A huge thank-you to István Steffanits, for whom nothing is impossible, as well as to the people in the Műcsarnok who coordinated the exhibition, for their excellent work.

January 2020

József Szurcsik

Munkácsy Award laureate fine artist

curator of the exhibition