Artonomy – Freedom of Art

József Gaál

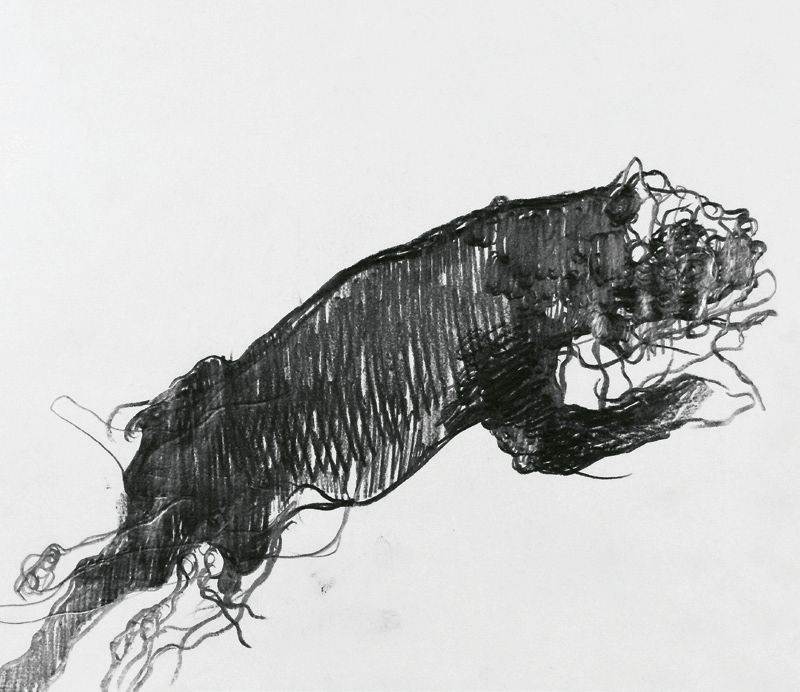

Gaál József: Macskák 1

2014, ceruza, papír

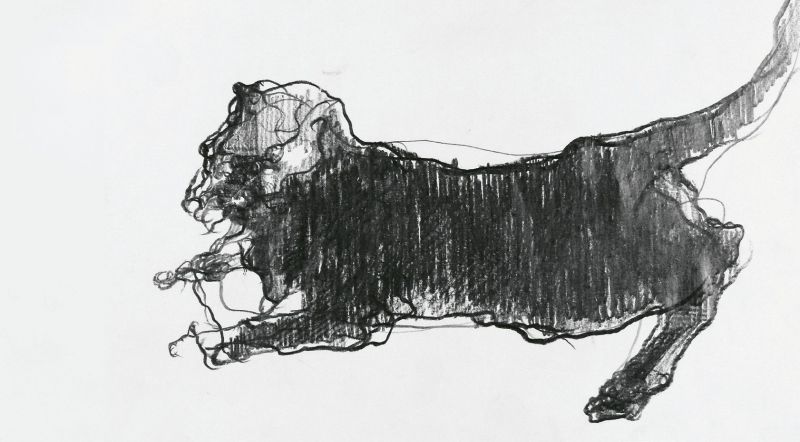

Gaál József: Macskák 2

2014, ceruza, papír

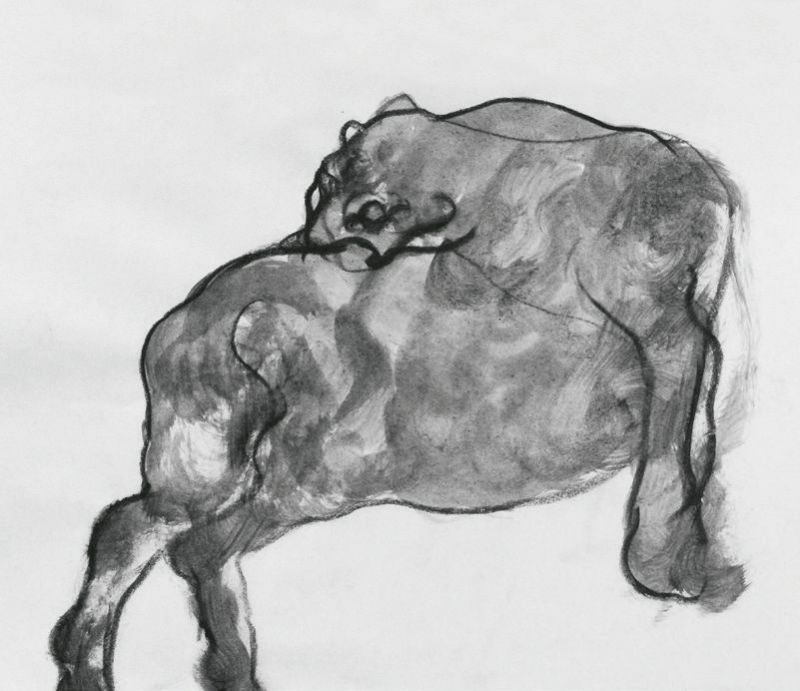

Gaál József: Macskák 3

2014, ceruza, papír

Gaál József: Macskák 4

2014, ceruza, papír

The title takes us right to the heart of the matter, the romantic ideal of art. The artist with the freedom of a child or some playful God, creating on a whim. Going from extremes, soaring out into the universe, then plunging Icarus-like into the deep. Kant sees the artist as a disinterested demigod playing alongside his beautiful dream argument. His autonomy makes him into a philosopher, a psychologist and later a psychoanalyst. But remaining with the romantic ideal, Schiller develops the strand of playfulness even further, seeing the artist as capable of creating his or her own world independently of any deities. The great player Goethe sees art as a second nature, at least as enigmatic as the original yet more comprehensible because – such is human self-awareness – the source of art is the intellect, because the universe is a turbulent mass that the artist simplifies to make it understandable, reduces to make it beautiful. It is true that the autonomous desire for art has given rise to its own metaphysics, creating its own idealistic aesthetic through the freedom of the artwork. This playfulness is no longer so autonomous and free, this game is about nothing less than the construction of a new world. Oh, deluded child – anyone who thinks they can create a new world with conjuring tricks is a Faustian magician, a charlatan doomed to failure.

So, where has this riff on playfulness train led me? To the game of changing the world: The messianic artist who wants to express everyone’s dream and actually make it a reality, play by his or her own rules, lead the struggle for freedom, shaping the new society with these games and freeing everyone in the process. But the people don’t want to wander around inside a constructed phalanstery. The romantic dreamer plays at engineering the transformation of the globe, all rational and pragmatic. The artist starts new games, agitates for the improvement of society, pretends that this is no game, no joke, but isn’t taken seriously. Nobody notices. Now the artist wants to play a serious game, like a rebellious child, eager to turn the world on its head. This arrogance was forced on the artist, who wanted to play but was shoved out into the arena, giving a boost to the ego. A gladiator is no longer a free player, no longer autonomous. Only in the arena does it become clear that the artist is merely battling is his or her own shadow. Awaking from the dream, the artist realises that he has pursued himself into this private arena of self-torment. Maybe the burdens of the romantic ideal still weigh heavy. First the independence originating from national pride, the awakening of everyone’s consciousness, then the liberation of every nation and race. What a grandiose pursuit! The artist fails to notice that there is a referee; indeed, a growing number of match officials marking out the playing field. This has always been the case, but while he was a child lost in his game he didn’t notice and didn’t concern himself with such matters. Why leave the playground now that he’s so engrossed in the game, he’s forgotten that it’s just something people use? Even now, he has to pretend to be a player in a team at one end of the pitch; the romantic ideal remains. The team of national romantics and the team of supernationals. The team of navel-gazing irrationals and the team of clear-thinking rational types, the traditionalists and the reformers. Those who put their faith in organic growth, and the constructing technicists; the list of made-up opposites could go on. All this is still romanticism, and perhaps even the game hypothesis itself is just a romantic idea. Is the game of these sweet, predatory kids not preparation for assassination, a coup? We started this discourse with Kantian beauty devoid of interest. We believe that beauty is a self-evident experience, but this is where the other game starts, the often-bloody game of the ideologies. How did the study of beauty become such a labyrinthine prison? Is the game spoiled, or is this the price of the freedom to play? Unconscious play is also an illusion, but the writer and carver of images wanted autonomy, and this longing for autonomy makes it necessary to constantly explain. What is the basis for this anyway – but the reins were taken out of the artist’s hands at the start; he is just a laboratory animal. Autonomy has a price, the science of aesthetics arranges and moralises, and never gets to the bottom of things because the animal pulling the cart bolts and the academic aesthete is thrown backwards into the spinach; or our theorist simply drives it into the quicksand of morality. And this is to say nothing of the seven veils obscuring the artwork itself: We only seem to suspect that there is something behind all those hermeneutic curtains. Yes, we are merely dumb lab animals; art has no autonomous system of values either theoretically or morally, so how could the artist! He is just a mimetic bogeyman who takes the game too seriously, believing that his imitations are creation. The theoretician has control of the ball of romance, he has become the transformer of the world; but doesn’t notice that the Great Referee of the World is not even laughing at this, because he can’t see it. He doesn’t remark that there’s a new player on the field, because he he’s playing on a different pitch altogether, which is out of bounds to those who play in the dust. The underestimation and overestimation of art made, and continue to make, the rules of the game: Sometimes science, as a systematic order, is what defines the quality of life and its moral foundations, while art only shows the superficial world of the present; at other times science may be soulless and pragmatic, while art creates a new world, a new humanity, from the depths of the soul and the intangible reaches of the intellect. This is a game too, the game of theories. Some fear the loss of art’s magic, some want to liberate it from irrational, bizarre and grotesque visions in order to attain a perceived clarity. A game or a battle, a sporting contest or a fight to the death? Do ideologies hide behind the game of art; or is the artistic structure, divested of its magic and removed from the game, intended to be used as a mouthpiece for the ideologies?

We wanted to discuss beauty, a game devoid of interests which the naive artist really would elevate to sanctity, because this is perhaps the only point where he still has a shot. Besides realistic unpleasantness, how many fantasy monsters, how much decomposition, death and casualties been born of the category named strange beauty! Art is a game of wisdom, and the wise confront the unsolvable, the indigestible, the invisible. A strange play, this monologue on the highly irregular games of the artist plumbing the depths of hell could continue indefinitely. This discourse on the self-sacrificial ritual games, the voluntarily invited tortures that overturned the elegance of the neo-classical aesthetic. An excess of passion for the game, the invoking of a denied God in the unconscious mind. We can’t escape into mystical unconsciousness, because psychoanalysis puts us right: The games of wayward children, a narcissistic window display of mental issues. So, bring on the taut self-restraint of art, where instead of carefree play the highly regulated game of scientific and aesthetic experience must be played! The fun is over; the principles of theory and practicality dictate that deriving objective understanding from a deep insight is a social obligation. You are an engineer, reconstructing the instruments of the souls drifting through society. A game should be educational. After the ritual and magic of the past we now see art’s function as psychotherapeutic role playing. The enactment and playful modelling of reality now divests the secondary game of its reality; it is merely an imitation, a mimicry of what is real. This game is just temporary, just as for children, too, it is a surface to be projected onto. A game of mimesis, copying, a grand illusion, a cleverly displayed model of reality. Mastering the tricks of illusion is a game for the conjurer. The perception of reality as a stable, external entity, and the subservient transience of art, has become fairly dogmatic; this down-to-earth game has is now just a technicist exercise. For many, the game and technique have spoiled carefree play as an ingesting and self-negating process, while others see in it the opportunity for renewal. There is no separate reality, no stable exterior to which the person interpreting the work can be trained. Now even the term interpreting seems strange, because to interpret one must have a stable base of knowledge with which to make judgements, with which to exclude, rule out and control. The essence of a large, shared game is the variable set of rules; the observers are also active creators, shaping themselves. This is why it’s irritating if the viewer expresses dislike of a work. Modernism is now about plurality, diverse artistic games, diverse sets of values; but in the eastern part of Europe – whether we see it as central-eastern or eastern-central – diversity was only desired. The free play of art can be revealing or an introverted, hidden internal game whose rules are known only to the initiated. If it is no longer a ritual, sacrificial game, let it be a mystery that one must struggle to solve. The esoteric game of art, the secret sign language, was not created by modernism. The imagined essence determines the path of exploration, the game played according to internal rules leaves no room for spontaneity, the unruliness that can give birth to a new rule may be born. A rigid game doesn’t permit crossroads, the irregularities in the between the regularities are what prevent us from being hobbled by our self-serving rules. Rule-following through free play, rebelling against the rules in the hope of creating a new rule. It is a myth that art has anything to do with the eternal order of the absolute, that it must be based on the infinite projection of some fundamental rule. Sure enough, these are the unknowable, changing rules of a labyrinth that can only be guessed at.

Rules and freedom – we believe that freedom of action in art is liberation from the rules, but there is no need to create a new system; just change the rules of the existing one, or a new rule can emerge from several others. Free play is nourished by the rules of the game. The different, the surprising, the completely new in art, the individual work, acting within the rules. Creative ability is fulfilment within the rules of the medium, even if this means creating a new regularity by mixing the media. Wittgenstein’s thoughts on play, when he talks about the web of similarities – and, we should add, differences – between card games and ball games, that can be categorised as some kind of “family resemblance”, are analogous to the now very broad category of art. The question is whether and to what extent professional wrestling, or a life-and-death struggle such as gladiator fighting, is a part of this martial art. Perhaps art also has a border region, and a region beyond its borders, that is no longer a space for play, no longer an artistic space. Art that is overly obligated, a thing called art that serves ideology, something that is no longer a game, no longer autonomous, but tries to be excessively pragmatic. Compulsory traditionalism, or compulsory “progressiveness”. It wants to educate by force, to be oppressively useful. Often it is not even the artwork, but the ideology foisted upon it, that no longer follows the rules of the game of art. A work of art cannot be autonomous, because it is a product of society – just like people themselves, we might add like undereducated post-Marxists. Free play is of no benefit; again, it needs to be re-regulated in the service of usefulness. We should bear in mind that by expanding the rules of the game, lots of things can be art, almost everything in fact. It spoils the playfulness if artists have to express their position in the history of art, or even to be deliberate shapers of art history. That is the end of carefree play, because the future has to be shaped with the expected intentions and a commitment to tomorrow. That is the end of the playfulness, the observer’s intimate immersive gaze that dissolves together with the artist in the observed work. The hidden truth that is a sensual experience, which is direct yet invokes something invisible and distant. As artists, we hope for some inexhaustible playground generated by the artwork with its special rules; but there are many games, many kinds of experience. Self-understanding is really an aesthetic game, because of the richness of meaning. Because of the meeting between the other world and our own, which ultimately lends gravitas to the game of chance because if the overturning of the rules is forced, affected, the artist is just a cheat. The rules are on the inside, the cult status of art is manifold, whether it occurs intentionally or involuntarily in the hope of a shared game. There is no timeless canon, no rule, no extra-historical norm. The spell of freedom, the eternal longing for mystical truth became fused together with pathos, but after the change we seemed to have become unaccustomed to a diversity of freedoms. The essence of common freedom is that others are not demonised for having a different view of their own freedom. The art of demonisation is not a sport, but the disregarding, indeed the nullification of the other’s opinion. There is no longer a playground or an arena; the faith placed in ideology excludes discourse and consideration from the one-sided game, and it excludes art that operates with ideas other than its own, and which it believes deserves to be vanquished.

To tie up the threads of this erratic train of thought the nature of art cannot be explained, given the throng of opinions that often contradict even themselves. Some look with awe at the past and reject the art of the present. Others, on the other hand, seek to uncover the past but already have a vision of the future. In fact, we all want the here-and-now reality but still always seem to dodge it somehow. This unexplainable thing swings between and sometimes beyond the reality of the moment and the mystery of the timeless, always creating the artwork differently.